“The healthiest competition occurs when average people win by putting an above average effort.” –Colin Powell

Table of Contents

Introduction

Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) contribute significantly to fostering well-rounded, inclusive, and fair economic growth and development. They achieve this by creating job opportunities and aiding in poverty alleviation, as recognized by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2004. MSMEs also help mitigate rural-urban migration by offering employment prospects in rural areas while promoting indigenous technologies. These enterprises serve as an initial phase for entrepreneurship and play a central role in a nation’s economic and social upgradation. They accommodate occupational mobility and contribute to the industrialization in remote regions, thereby reducing regional disparities and fostering equitable distribution of income. Furthermore, MSMEs serve as valuable complements to large industries as ancillary units, underscoring their indispensable role in a country’s socioeconomic advancement[1]. The generally prevailing understanding is that MSMEs are prone to falling into the trap set by the other big players in the market as they are largely unorganised and vulnerable to the dynamic external business environment.

The Competition Commission of India has the power to govern these enterprises, whereby they are vested with the power to prevent anti-competitive agreements and prohibit anti-competitive practices and abusive market conduct by dominant players in the relevant market. The Act majorly focuses on providing an equal playing field in the market for every enterprise and industry irrespective of their size and financial position thereby ensuring equal opportunities to take part in the economic growth[2]. While the Act does indeed protect economic opportunities for SMEs, it’s essential to acknowledge that SMEs are also bound by its regulations and provisions. The Competition Act of India applies to both large industries as well as SMEs, making them equally accountable for any actions that hinder fair competition.

Definition

MSMEs, which stands for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, are self-explanatory in their full form. They refer to small and medium-sized entities within our society that operate on a minor scale in laissez-faire capitalism, i.e. free market economy, thereby representing the most significant group of undertakings[3].

The criteria for categorizing small and medium enterprises (SMEs) vary from one economy to another. Many countries do not distinguish between micro and small enterprises, focusing instead on differentiation among small, medium, and large enterprises. Those that do make distinctions often use specific factors such as employee count, annual sales, turnover, or investment in machinery and equipment.

In India, the classification of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) was established under Section 7 of the MSME Development Act of 2006. However, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Cabinet Committee approved a revised definition of MSMEs via a notification[4] on June 1, 2020. Under this new definition in India, both investment and turnover are employed as standardized criteria for classifying MSMEs[5].

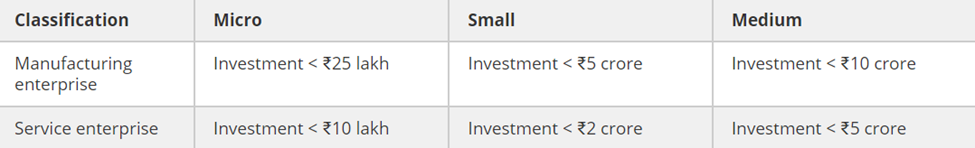

PRE 2020:

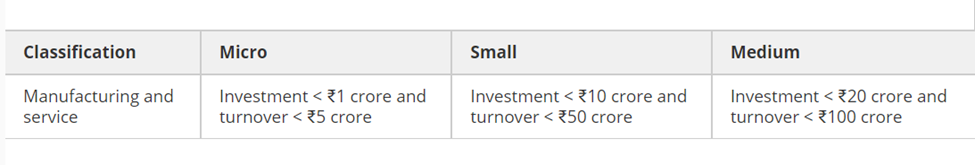

POST 2020:

Importance of MSMEs

From an economic perspective, MSMEs contribute over 35 to 40% of India’s GDP, thereby known as the “Engine of Growth” for all developing countries, which also includes India. Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) play a vital role in providing job opportunities to the most vulnerable and economically disadvantaged segments of society, offering them a path out of persistent poverty. They are a significant source of immediate, widespread employment, requiring lower investments, and stand as the second-largest employer, following agriculture, thus holding a prominent position in the economy[6].

MSMEs not only fulfill a crucial role in creating vast employment opportunities at a lower capital cost compared to large industries but also contribute to the industrialization of underdeveloped regions. According to reports[7], the MSME sector accounts for about 45 percent of the manufacturing output and 40 percent of total exports in the country. It provides jobs for approximately 80 million people through 36 million enterprises nationwide, manufacturing over 6,000 products ranging from traditional to high-tech items.

MSMEs exhibit a higher labor-to-capital ratio and overall growth compared to large industries. Additionally, they are geographically distributed more evenly across the nation. Consequently, MSMEs play a pivotal role in achieving national objectives of fostering growth with fairness and inclusivity[8].

MSMEs – always a victim?

The MSME sector in India exhibits significant diversity concerning the enterprise size, technological levels and the range of products and services that are being offered. A notable portion of Indian SMEs operate in sectors such as retail trade, machinery, leather and textiles, often coexisting with larger enterprises. However, smaller businesses engaged in the production of goods suitable for mass production face a considerable challenge, as larger firms can manufacture such products more efficiently by benefiting from economies of scale. In situations where size confers advantages in purchasing, production, marketing, and distribution, MSMEs find themselves at a disadvantage compared to larger counterparts.

The interaction between SMEs and large corporations can occur at different points along the supply chain. On one hand, SMEs serve as suppliers to large enterprises, providing items like automotive components. On the other hand, they rely on large corporations for their input materials or raw materials. Frequently, SMEs feel that, as suppliers, they are mistreated by large corporations, which often delay payments for supplies beyond agreed contract terms. Since SMEs depend on these large corporations for their survival, they sometimes reluctantly accept unfair terms[9]. When they act as buyers of products from large enterprises, these smaller firms incur high costs due to their limited negotiating and bargaining power. Consequently, these small enterprises contend that their size puts them at a disadvantage.

Such an instance has been illustrated in the Auto Parts case[10], wherein (CCI) determined that 14 car companies were responsible for exploiting their dominant position within their relevant market with respect to the supply of spare parts. As a consequence, a substantial penalty was imposed on these companies. It was also found that these companies engaged in restrictive trade practices by refraining from making their original spare parts available in the open market. Additionally, they failed to provide essential information concerning tools and technology necessary for carrying out repairs. Consequently, this behavior resulted in the exclusion of independent repairers from accessing the market, as they operate within the open market that deals with servicing and spare parts[11].

MSMEs as perpetrators

The general notion is that MSMEs are consistently seen as the victim of abuse by dominant players in the market, thereby aiming to eliminate these enterprises. It is a well established fact that the small size of the MSMEs makes them vulnerable to anti-competitive acts of bigger enterprises. However there exists a dilemma in understanding the other side of the coin, whereby MSMEs enter into cooperation agreements amongst themselves to tackle such situations. In the process of overcoming such difficulty, they form cartels in order to compete with such large enterprises, which does not always conclude in their favour. It should be noted that these enterprises come together and collectively work, which makes them the dominant player in the market. They later abuse their dominant position, thereby exploiting the customers. As discussed earlier, Competition law is size neutral, henceforth MSMEs are still bound by such limitations that are laid by the CCI.

In order to support the above contentions, it is important to prove the same with recent cases wherein, it was resulted that the MSMEs are the problem-creators in the first place, rather than being a victim always, these cases are entailed from the fact that MSMEs have another side, which the commoners have fail to determine. In the case of M/s Shivam Enterprises v. Kiratpur Sahib Truck Operators, Cooperative Transport Society Limited, and its members[12], it was noted that the MSMEs (Opposing party) had established a dominant position and restricted any other service provider than that of its members from offering freight transport services in a specific region. Moreover, the pricing set by these MSMEs were rigid and non-negotiable. The members of such MSMEs had also used force against the other party to prevent them from executing their contracts, leading to a denial of access to the market for others. Consequently, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) found that the MSME had violated Section 3 and 4 the Competition Act, which deals with anti-competitive practices and the abuse of dominant position respectively. As a result, the CCI imposed penalties on the parties based on their average income from the last three financial years.

In the case of the Bengal Chemist and Druggist Association[13], the Competition Commission of India imposed hefty penalties on the BCDA due to their anti-competitive actions. This case was initiated by the CCI on its own accord (suo motu), where it was observed that BCDA, an association comprising wholesalers and retailers, engaged in coordinated efforts to fix drug prices. It was also noted that BCDA had instructed retailers to sell drugs at the Maximum Retail Price set by the association on their own which is based on an agreement reached among its members. Additionally, BCDA conducted investigative operations to identify retailers who did not comply with the directions given by them, and it was compelled that those who defied the association’s instructions were ordered to close their shops as a punishment. The CCI also held the senior office bearers personally accountable for participating in such anti-competitive activities on behalf of the association.

Bid rigging, an anti-competitive practice, involves enterprises collaborating together and pre-determining which one(s) will win that particular bid. Typically, these schemes are combined together to create the appearance of a competitive process while, in reality, stifling actual competition. Bid rigging is one of the major concerns that is in existence, especially for government departments, as there are schemes relating to the procurement of goods and services from non-state enterprises in order to encourage such small enterprises. Under the Competition Act of 2002, bid rigging is treated as a serious offense and can be considered illegal per se, even without any harm being caused because there are no justifications for such an act, considering the repercussions it may hold in the relevant market and the economy as a whole[14].

In the instance where, The Union of India, represented by the Secretary of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, issued an invitation for bids for the supply of prefabricated modular operation theaters[15]. Six parties submitted their bids, and the committee favored the bid submitted by PES Installation, even though it had a technical deficiency. It came to light that three of the bidders – MPS, MDD, and Unniss – did not possess exclusive authorization for the integration of modular operation theaters. Both MDD and MPS were aware of this fact but still participated in the bidding process to assist PES in winning the bid.

As a result, the actions and behavior of these three firms were considered to be part of an overall agreement among them which was known to be a Cartel. Under this agreement, they had decided to take turns bidding on contracts in different hospitals, which would put them at a better stage of profits, thus not allowing outsiders to participate in the market. Given that the Competition Commission had already imposed penalties on these three parties in a similar case, it did not find it necessary to impose any additional penalties in this instance.

Conclusion

As per the recent widespread news regarding the plan of the Central Government to establish a training center worth Rs. 200 Crores in Goa in order to support the working of MSMEs[16], this statement was in itself expressed by the Chief Minister of the State in the NITI Aayog’s workshop on women-development. Therefore, it is to be understood that even though it is well established that MSMEs are at a vulnerable position to the abuse rendered by the larger players in the market, they are not always the victims, but they do tend to misuse the vulnerability against others. Henceforth, while making any allowance relating to MSMEs, the legislature or the Central Government should keep in mind the repercussions it might hold, considering the fact that MSMEs are capable of abusing their vulnerability.

This article has been authored by Adhira S., a student of Christ (Deemed to be University) Pune.

[1] https://reviewsep.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2_ALLAMRAJU-Arranged.pdf

[2] http://www.wasmeinfo.org/smes-and-competition-law-worth-exploring-the-linkage/

[3] https://www.raijmr.com/ijrhs/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/IJRHS_2016_vol04_issue_05_05.pdf

[4] https://msme.gov.in/sites/default/files/MSME_gazette_of_india.pdf

[5] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09708464211037485?icid=int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.3

[6] https://www.raijmr.com/ijrhs/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/IJRHS_2016_vol04_issue_05_05.pdf

[7] https://msme.gov.in/report-working-group-msme-growth-12th-five-year-plan-2012-17

[8] https://www.journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/9680

[9] https://reviewsep.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2_ALLAMRAJU-Arranged.pdf

[10] Shamsher Kataria v. Honda Siel Cars India Ltd. and Ors, Case No. 03/2011 of Competition Commission of India

[11] https://reviewsep.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2_ALLAMRAJU-Arranged.pdf

[12] Case No. 43/2013 of Competition Commission of India

[13] W.P. 29014 (W) of 2017 – Bengal Chemist and Druggist Association and Another. V. The Competition Commission of India and Others. 2017 SCC OnLine Cal 20337

[14] https://reviewsep.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2_ALLAMRAJU-Arranged.pdf

[15] Pes Installation (Pvt.) Ltd. vs Corporation India Ltd. – Case no. 43 of 2010 of Competition Commission of India

[16] https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/centre-to-establish-rs-200-crore-msme-training-hub-to-in-goa-cm-pramod-sawant/cid/1970765

All efforts are made to ensure the accuracy and correctness of the information published at Legally Flawless. However, Legally Flawless shall not be responsible for any errors caused due to oversight or otherwise. The users are advised to check the information themselves.